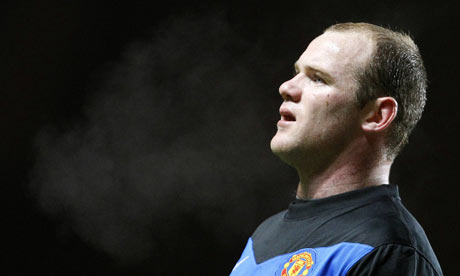

In a Dublin bar they were showing Wayne Rooney dazzling Milan on a big screen at one end and Cristiano Ronaldo going out of the Champions League at the other. As they rubber‑necked to watch both spectacles, some of those drinkers looked as if they had seen a few alehouse visions of heaven and hell in their time.

But these competing pictures glowed with revelatory force. If you had stopped the football carousel for five minutes on Wednesday night you might have said that Ronaldo screwed up by joining the new Hollywood studio that is Real Madrid and that Rooney has come of age in his absence. Another insistent thought took hold: Wazza is infinitely more influential than Gazza in elite competition and is surely the most potent English footballer since Bobby Charlton.

This is a logic game, not one born of superficiality and giddiness. To think it wrong to say that Rooney is the best since the embodiment of the English game around the world you would need to propose a credible alternative. Running through the lists since 1966, I picked out a few contenders: Kevin Keegan, Bryan Robson, John Barnes, Glenn Hoddle, Alan Shearer, Paul Scholes, Michael Owen, Frank Lampard, Steven Gerrard and Paul Gascoigne, a comet who troubled the firmament at one international tournament (Italia 90) and is over‑venerated for his goal against Scotland at Euro 96, when he was already clinging to the wreckage of his talent. Gascoigne's club career, meanwhile, featured a year or so of reckless brilliance at Tottenham Hotspur, then ever-decreasing circles at Lazio and all points beyond.

To think: people wrote earnest columns about Rooney's potential for Gazza-esque burn-out whenever he picked up half a lager in an Alderley Edge bar or swore at a referee. There is another dissertation to be written about Rooney and social mobility: how he was cast in his early days as a street thug who had wriggled through the economic cordons of our inner cities to present himself as the butt of middle‑class jokes. Germaine Greer, remember, said he had a face like a clenched fist: a line much repeated, no doubt, by the sort of football arrivistes parodied so well by Paul Whitehouse.

Rooney has transcended bourgeois condescension to exemplify many of the attributes that we think we have as a nation but do not really. Innate talent, a compulsion to improve one's lot and complete selflessness are qualities found in those excruciating speeches Gordon Brown likes to make about British characteristics. You don't get these attributes from a passport. The wonder of Rooney is that there is not a professor in the land who can explain why one lad from a large family is blessed with the talent and the appetite to chew the best opponents up and spit them out at the very top of a hard profession.

On that scroll of candidates for the title of best-since-Charlton there are several who could win games on their own through force of hunger or ability. How many matches has Lampard shaped for Chelsea? Was Robson not Roy Keane but with greater attacking prowess? No English player since Charlton, though, has had such a transformative effect on club and country as Rooney has this year. England's greatest go bald early and bestride Old Trafford: that's just the way it is.

The nature of the man is endlessly intriguing. Gary Neville told in these pages last week how Rooney craved the arrival of England's game against France at Euro 2004. The boy wonder was supposed to be petrified. Neville thought it "strange" that hellfire burned in his young colleague's eyes. He knows, now, why the flames danced. Rooney's brand of conviction cannot be bought in JJB Sports.

Neville also says: "There aren't many players who can play on their own up front and be successful. Rooney is one, [Didier] Drogba is another. Louis Saha does it very well. Other players need a foil." Thrust into a supposedly lonely role, Rooney has struck 30 times in all competitions and could surpass Ronaldo's 42 goals from two seasons ago if United play 14 mores games and he appears in them all.

The PFA and Football Writers' Association player of the year awards are such a formality that the vote counters may as well take this year off. And those Iberia-based princes, Ronaldo and Lionel Messi, must be feeling Croxteth's breath on their neck in next year's Fifa world player poll.

Charlton scored 49 times for England (Rooney is halfway there, on 25) and has 1966 to preserve his international lustre. He has also served as the English game's symbol and elder statesman for longer than Rooney has been alive. There is no cause yet to chip away at his statue. Sore knees could yet slow the whirlwind's progress through this first post-Ronaldo campaign and there remains the remote possibility that he could feel sated by his late twenties.

But this is a burnished figure in world football: a self-made master of the physical and psychological arts. The country is mesmerised. Tribalism is on hold.