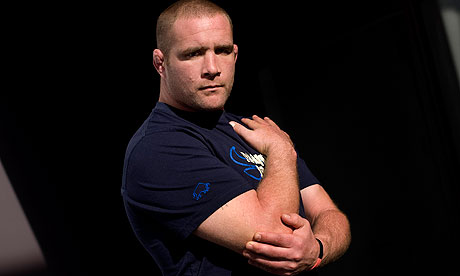

Phil Vickery's shoes say much about him. There is a hole in one of the soles and the heels are badly worn but there remains a certain battered quality about them. Closer inspection reveals they are the same butterscotch Oliver Sweeneys supplied to the 2003 World Cup-winning squad. They could easily serve as a symbol of the long, hard road English rugby has trodden in the intervening seven years.

So, too, does Vickery's newly published autobiography Raging Bull (HarperCollins, £20). How long will it be before another English prop forward has publishers fighting over his life story, a tale so soaringly inspirational and brutally painful that printed words struggle to do it justice? As the Cornishman gazes around his publishers' modern offices in Hammersmith, you wonder whether the bright young things at their keyboards fully appreciate the punishment their latest author has absorbed. England have had few more endearingly stubborn captains, nor a player who put the "grit" into integrity more often.

The question now is whether he has one last massive shove left in him. At the age of 34, after a succession of back operations and other surgical procedures, he still wants to play international rugby – "It is a drug … of course it's something you want to do" – but an attack of shingles has forced him to sit out Wasps' opening Heineken Cup pool encounter in Toulouse on Sunday. With Dan Cole, David Wilson, Paul Doran-Jones, Alex Corbisiero and the suspended Matt Stevens all aspiring to play tighthead at next year's World Cup, it is going to take something pretty special for Martin Johnson to overlook all the younger pretenders.

"I've spoken to Johnno a couple of times," Vickery says. "If my form warrants him changing the blokes he's got, he'll do it. Simple as that. That's the only way I'd want it. If fit and playing well I'd love to be part of another World Cup. I didn't want lots of tributes in the book because I don't consider my career to be over. I'll always want to play for England."

An hour spent with Vickery, either way, is to be reminded how lucky successive England coaches have been to have him. There is a nice anecdote in the book about his first training session for Redruth, who had just lured him down from Bude. The teenager arrived late after helping with the milking chores on the family farm and, as he came over a small hill towards the rest of the players, appeared to block out the sun behind him. "It was like a scene from a film," one of the coaches told him later. Soon enough he was playing senior rugby against Newbridge and Dunvant on wet Wednesday nights, a post-match roll-up in one hand and a pint of Guinness in the other. The local paper dubbed him "The Dude from Bude" and he was playing for England at 21.

Almost 13 years on, he remains a devoted fan of Take That – "I bloody love Take That and I don't care who knows it" – and is now waiting for English rugby to regroup and reconquer the global charts. "I watched a lot of those England matches [last season] and thought to myself: 'I don't think some of the guys are good enough. To be an international player you need to do more,'" he writes.

Did England's victory over Australia in Sydney last June not alter his view? "Let me put it this way. Take the second Test out of the equation and what has changed from the England of 2006? What has really changed? There's a lot of talent out there, it's just how you bring it all together. You've got to want to be the bloody best. It's about making sure people are motivated to think like that."

If this sounds like a gentle dig at his old mate Johnson, he insists otherwise: "You see so many good men chewed up and spat out by the game. As a friend, I wouldn't want to see that happen to him."

English clubs, he also suspects, will again have their work cut out in Europe this season – "I think it will be French again, I really do" – and he is convinced the sport has entered a crucial phase in terms of its public appeal. "I want someone to walk past a TV screen in a shopping mall, look up at the screen and say: 'Jesus, I want to watch this.'"

Could that ever mean sanitising the scrum in the interests of continuity? "There will have to be some sacrifices to consistently produce that sort of product." You can hear the mutters in Redruth already.

Vickery, though, has always been honest to a fault. It would have been easy to rewrite history and airbrush the scrummaging problems which cost the Lions dear in the first Test against South Africa last year. Instead, contrary to the bullish title, there is barely a hint of rage to be found within the book's 287-odd pages, aside from a brief swipe at Stuart Barnes's punditry and a revealing paragraph or two about his parents' divorce. He prefers not to go into grim detail but his eyes still moisten at the memory a quarter of a century later. "It does change you, it does affect you," he says softly. "It makes you tougher and less trusting of people. It makes you harder and I know I've carried that with me."

It also helps explain why he resisted any temptation to settle old scores in print. "You can end up turning into a bitter old twisted git and I never, ever want that. Why should I go on about other people's failings when I know I've got failings of my own? I think I've got a lot of people's respect. You can end up wiping that out for … for what? A bit more money and some good PR? All I want is for people to read the book and not get a headache from trying to understand it."

If nobody buys it, he will simply remind young players that character counts for more than money or fame. "Phil Blakeway always used to say you find out who your friends are when you're lying on the bed, you can't move, you can't even have a shit and the phone's not ringing. That is the reality of what we do." Phil Vickery? Dog-eared old loafers, quality human being.