It began on 9 September, far too long ago. And after all the energy and expense and the dwarf-throwing, all the injuries, the boasts, the headlines, and the gruesome Haka encores, they say the whole Kiwi caboodle is bound to end this Sunday in a discordant anticlimactic mismatch.

Who, anyway, remotely expects the World Cup final to be an all-singing, all-dancing spectacular? They never are. World Cup finals have no rich pedigree, no vivid provenance of colourful or inspiring back-story to bank on.

The very first final, in this same town and between the same teams as Sunday, was a turgid home-team walkover: New Zealand 29, France 9. There were four tries – undistinguished, long-forgotten things maybe, but at least there were four, twice as many as in any other final.

In the five finals since that humdrum premiere in 1987 only five tries have been scored – by Tony Daly in 1991, Owen Finegan and Ben Tune (1999), Jason Robinson and Lote Tuqiri (2003) and, er, that's it. Not one stirred the blood. Who can remotely remember any details? In six World Cup finals, 188 points have been scored, a grotesque 148 of them from kicks. In two of those finals (1995 and 2007) a total of 48 points were logged, but not one solitary try was scored.

Wales is in a red mist of recriminations about an Irish referee, but Wales lost Saturday's semi-final not because they played with a man short, but because they couldn't pot a handful of place-kick sitters. Or even manoeuvre a fly-half into a safe-option position for a wretched drop goal. In wantonly blowing all those gifts, Wales actually proved kicking's utter pre-eminence.

The two fabled fly-halves of my boyhood were Ireland's Jack Kyle and Wales's Cliff Morgan – octogenarians happily still with us. In an eight-year Test span, Cliff never dropped a single goal, and in all his nine years only at the very last did Jack just once "pop over a wee one simply to show Dublin I could".

British schoolboys in the 50s and 60s revelled in thrilling tales of resplendent tries – for the English at Twickenham, for instance, by Peter Jackson in 1958, Richard Sharp in 1963, and Andy Hancock in 1965 – or thunderously reverberating tackles at Cardiff – say Clem Thomas on Jeff Butterfield (1955), Haydn Mainwaring on Avril Malan (1960), and Alun Pask on Walter Spanghero (1966).

Then, slowly, the romance of the extemporary instinctive open-field strike was left to fade. It is 40 years precisely since I came back to these pages after a cheery diversion with ITV and as soon as I returned to the wintry press boxes, I was increasingly chronicling not the breathtaking touch-line dash, the hopscotch sidestep, the ravishing inside break, the sandbagging tackle nor the courageous, geometric corner-flagging. Instead I found myself making heroes of the dead-eyed Dicks, the potshot Pauls, the leathering Lens, the hoofers and their howitzers.

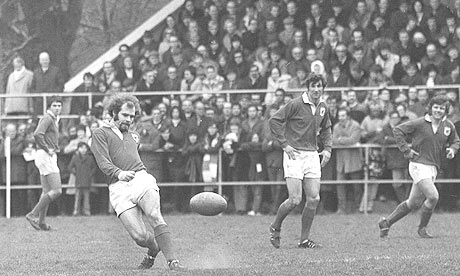

You could even say it began in dewy-eyed innocence that February afternoon of 1971 at Murrayfield, with "the greatest conversion since St Paul". TalkSport's chief commentator down in the southern seas, John Taylor, was not Wales's regular kicker, but who can forget that tea-time gloaming when he insouciantly soft-shoed up in the last minute with a left-foot inswinger from the right touchline to win Wales a Grand Slam and set them on their irresistible decade of the dragon.

That summer no end of Taylor's compatriots helped the British & Irish Lions to, still, their most glittering and imperishable triumph, the New Zealand Test series being sealed 2-1 only at the end of the final match in Auckland by JPR Williams's monster drop goal from 45 yards to make it 14-14.

The era of the boot was verily here to stay. The next most ravishing red-letter Lions victory, in South Africa in 1997 (the overblown 1974 win there was against pallidly unready opposition), was also settled with the last stroke of the series and Jeremy Guscott's instinctively snatched drop goal.

By which time the World Cup was very much the game's quadrennially ascendant showpiece – and on those same South African fields two years earlier we had remembered the periphery parts played by old Nelson Mandela and young Jonah Lomu.

When it comes to winning strikes, however, far more vivid for history were three successive hoorayinghoofs in turn by Rob Andrew, Zinzan Brooke, and Joel Stransky; predictable drop goals every one – and, ah me, a clutch of deciders almost as indelibly engraved in the mind as the signature swing of Jonny Wilkinson's boot at Sydney in 2003. Is there anything else to remember?

Still, set your alarm for Sunday. Rugby Bootball for ever.