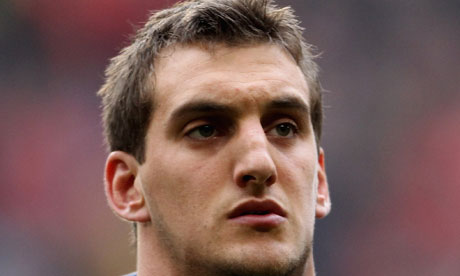

Given his performances on and off the pitch since Wales's arrival in New Zealand, Sam Warburton may have been the last player anyone would have wanted to see brought low by such a calamity. But fate had other ideas, and to cope with the consequences of his sending‑off against France he will need all the level-headedness that was so widely admired as Wales made their impressive progress to the last four of the 2011 Rugby World Cup.

As France celebrated their extraordinarily fortunate passage to a third final, Warburton rejoined his team mates for a slow lap of the pitch, saluting fans who had clung on to the hope of victory until the very last moment of the match, when Wales, after putting together more than two dozen phases just inside the France half while trying to manoeuvre Stephen Jones into position for a final drop‑goal attempt, let the ball and the result get away from them. The captain's black puffa coat resembled a shroud.

Sometimes sport is a cruel master and it seemed desperately unfortunate that the 23-year-old captain, the object of such a crescendo of praise in the days leading up to the match, should have become the central figure of the contest's pivotal incident. Whatever the rights and wrongs of Alain Rolland's decision to send him off for a tackle on Vincent Clerc after 18 minutes, it was impossible not to feel sympathy for a young man who had been held up as a symbol of the restoration of Wales's belief in itself as a rugby nation and who will have a big role to play in its future.

Yet the fact remains that Warburton drove Clerc into the air in such a way as to turn the French winger upside down, and then let him go so that the opponent fell on the back of his head and his shoulders. Under the rules, dropping the tackled player in such a situation is as bad as spearing him into the ground, which was why Mr Rolland took out his red card.

Clerc was not hurt. There was no sign whatsoever that Warburton intended to do him harm. And similar tackles are often punished with a yellow card rather than an outright dismissal. But none of that matters. Rolland was upholding the letter of the law, in response to the authorities' explicit instructions to deal firmly with the aspects of the game that are most likely to cause grave injuries. Outcome, intent and precedent are immaterial. Those who know players who have been badly injured in similar circumstances will no doubt be applauding the decision.

Everything about the incident was unfortunate, particularly its choice of context. The play had been relatively shapeless up to that point, the nervous incoherence of both sides a clear indication of the significance of the occasion. Had all 30 players remained on the pitch, no doubt the game would have settled down, with a pattern emerging. As it was, the last hour of the contest was shaped by the increasing adventurousness of 14 brave Welshmen as they tried to batter their way through an obdurate French defensive live with an urgency that increased as it became obvious that their kickers were not going to help them complete the job.

Wales had 60% of the territory and much closer to 100% of the skill and initiative on view. Once they had come to the realisation that their best chance lay with the ability of their power runners – Mike Phillips, Jamie Roberts, Toby Faletau and George North – to bash holes in the French cover, they were magnificent. When the pain of failure has finally ebbed, and that will take some time, the memory of the spirit they displayed in defeat may prove a touchstone for their further development.

France could have played until Christmas without coming close to scoring a try, even against depleted opposition. A couple of midfield breaks by Morgan Parra, one in each half, were virtually all they gave to the match in terms of flair and entertainment. Otherwise they relied on Parra's flawless kicking to secure the victory.

How ironic it seems that Wales, the land of the No10 factory, should have been unable to prevail in such an important match because two fly-halves – albeit the first and second reserves in the position – failed to land their kicks, either with a stationary ball or out of the hand. James Hook missed two kickable penalties out of three before being replaced by Stephen Jones, who was denied the opportunity of a penalty and failed to seize the chance of a drop goal with 10 minutes left to play. Finally, in the 76th minute, came Leigh Halfpenny, the long-range specialist, whose effort from the halfway line fell under the crossbar.

Warren Gatland and Shaun Edwards have given their Welsh side a rational structure and a solid mentality reminiscent of an All Black team. What is lacking – in the absence, perhaps, of a Gavin Henson – is the unpredictability that would have dismantled France's hard-working defence in the closing stages.

By restoring a touch of genius to their painstakingly constructed machine, they can ensure that the story did not end on Saturday night.